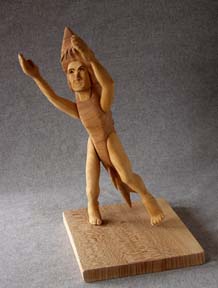

Sturgeon Leaps

Sturgeon was in deep. But even in the deepest dark channel of the Kennebec the waters were warming up. The Sun was high, the days were getting long, and the surface waters of the estuary and all its branches were basking in the late spring sunlight. Feed was in bloom and Sturgeon’s world was a seething soup of New Life. Sturgeon had seen it all before. He was a wise old fish of considerable weight and experience. Not that he approached the gravity of his storied ancestors. Sturgeon was six feet six inches long, from snout to tail fin. A giant in today’s Bay, but hardly measuring up to the 20-footers of old. Still, he was the biggest fish in the Sagadahoc and local lore-master among the finny tribes. |

Those tribes weren’t what they’d been, either. Salmon and shad were mostly memories, although the alewives were coming back. Glinting night passages of alewives, rushing upstream to hurl themselves at the falls, had stirred Sturgeon’s sleep all month. Eels were scare since they’d cleaned the rivers and skimmed off all the elvers, but Weird Eddy was still making whirlpools out in Chops, and hanging out down to the cannery.

It was mostly the young sturgeon and stripers who came around looking for wisdom, these days, or maybe a golden carp or an inquisitive perch, if Sturgeon was cruising in the fresh water. Sturgeon generally stuck to the Kennebec deeps, however, where a tongue of salt water pushed in under the fresh runoff. Sturgeon liked the density of the deeps, and the salt tang.

Sturgeon’s favorite deep hole was out by the end of The Sands, where all the river currents meet in merry turmoil. Here Sturgeon could taste all the news of the Kennebec, and the Androscoggin, and the Abigadasset, and the Cathance, and the Muddy, and the Eastern rivers – and all their tributaries. All the tales and treats of the upper reaches would come sifting down to Sturgeon’s deep.

This Spring the tales had been good. The freshets had flushed prime feed into the waters, and the bug count was definitely up. It smelled like a profitable year upstream. There was still a disagreeable tinge of mercury and dioxin spilling out over the Androscoggin sand bars, but nothing like the old days. Sturgeon could tell when they were pumping the ponds above Pejepscot by the way the yellow foam tinted the moonlight, and he could taste new developments up the Cathance, but nothing too disgusting.

“Same old, same old,” Sturgeon grumbled to himself.

Even so, there was something in the waters that tugged at Sturgeon’s consciousness. Some niggle of hidden knowledge tingled his barbels and rattled his bony plates. Sturgeon figured on it, tried to fathom it, but it eluded him. Sturgeon circled in the deep.

This fine sunny day Sturgeon was slowly cruising below the lip of the Androscoggin overfall close in to Sturgeon Island. Dragging his barbells through the ooze, and pushing his great tubular mouth out to slurp up annelids and the odd mussel. Whatever was nudging the back of his mind was particularly insistent. Was it the faint trace of something new in the waters, or the echo of some distant memory. Either way, Sturgeon was distracted. Sturgeon circled in the deep.

Now Sturgeon has three ways of watching the World. His snout and barbels sniff the soup around and below him, and lead him to his lunch. His whole body senses the current streaming past, and vibrates with the music of the deep. Then there are Sturgeon’s eyes. While Sturgeon wends his way through the turbid depths, tasting the tide and feeling the beat, his eyes look up to the filtered light above. Sometimes a floating delicacy crosses his view, and Sturgeon will spiral up to slurp it down. But mostly Sturgeon watches the play of light by the surface, for the joy it brings him. Sturgeon is a deep old fish, and he ponders on the wonders of the Light. Sturgeon circled in the deep.

This day Sturgeon wasn’t alone in his foraging. He’d noticed a pair of young catfish prowling in his wake some time since, but now they were edging closer. Sturgeon quite liked these newcomers. The blue catfish had been introduced in lakes and ponds upstream, where they were expected to winter-kill, but they had escaped into the estuary. Now they were multiplying rapidly. Sturgeon liked the sound of their Southern accents, and was flattered they so often turned to him for advice about his world – a new world for them. Sturgeon circled in the deep.

Sure enough, both young catfish came up alongside to query the old fish.

“Good morning, Master Sturgeon?” one catfish began politely.

“Mmmm?” Sturgeon responded, still half in muse.

“And how does your corporosity sagaciate this fine morning?,” the other catfish drawled.

“Finest kind,” Sturgeon observed gruffly, he voice croaky with disuse.

“Master Sturgeon, we don’t quite understand something,” the first catfish said. Sturgeon nodded encouragingly.

“We see the young sturgeon leaping up out of the water, and we can’t cogitate why.” Sturgeon flicked his tail back and forth. Like all good teachers he encouraged his students to think for themselves. “Why do you suppose they do it?” Sturgeon asked. The catfish cast uncertain glances at one another. |

“Well…” one began, and fell silent.

“Mmm ?” Sturgeon prompted.

“Well…” the second catfish chimed in, “we’ve heard it bandied about that…” here the catfish paused. The other hurried to conclude “… that sturgeons can’t fart under water.”

There was a dead silence. Then Sturgeon roared with laughter, and thrashed his tail in hilarity. He laughed and thrashed and thrashed and laughed until he’d stirred up a great cloud of silt that half-choked him and the Catfish. Then there was a thunderous noise from Sturgeon’s backside and clouds of bubbles went galloping to the surface.

“Guess not,” the catfish said in unison, between giggles.

It took a long time for Sturgeon to regain his composure. As he calmed down and the silt settled, Sturgeon again felt that tugging at the back of his mind. It set him in muse. Sturgeon circled in the deep.

When his attention returned to the here and now, the two Catfish were still in attendance, quizzical smiles on their faces.

“Excuse me, I must be getting old,” Sturgeon said. “You were asking about the Sturgeon Leap.” He paused. “You see, we do it because of a very old tale – one that comes from the famous caviar days, back in the times of the great 20-footers.”

The catfish gabbled back and forth in excited whispers.

“Yes, 20-footers. There are even stories about 30-footers, but I think they must be myths,” Sturgeon said.

“Anyhow,” the big fish went on, “the tale goes that the Great Mother Sturgeon of those days fell in love with Kingfisher.”

“Kingfisher?” one of the catfish asked.

“Yes. He’s an iridescent blur bird that hunts here in the summertime,” Sturgeon continued. “We sturgeons love to watch the play of light on the surface of the water, and Kingfisher makes a spectacular show when he dives in.”

“Back in those storied days the Great Mother Sturgeon was so enchanted by the Kingfisher’s diving display that she felt she must show the beautiful bird her own magnificence. So she swam round and round, faster and faster, until she was racing at hull speed, then SWOOSH she shot straight up out of the water. Her gorgeous immensity rose up in the air like a missile, then came down with a crash like thunder.” “Kingfisher was suitably impressed, as who wouldn’t be to see the Great Sturgeon in all her glory. He in turn dove into the water and did a dazzling dance. It filled the Mother Sturgeon’s eyes with kaleidoscopic visions.” |

“Each sunny day the two lovers would leap

and dive for one another, and the whole Bay watched in admiration. But then

the Sun declined, and it came time for Kingfisher to fly South, and for the

Great Mother Sturgeon to seek her winter deeps. For all their dancing together,

they had hardly shared a word, and now they couldn’t find a thing to

say.”

“Kingfisher stayed on until there was ice in the backwaters and the

baitfish scarce, but he finally had to go. They say the last pas de deux the

lovers danced were spectacular – leaping and diving in synchrony in

the low-angled sunlight, while all the creatures sang. Then he was gone.”

“The Great Sturgeon spiraled down into the murk of the nethermost deeps

and cried out her sorrow. Her lamentation was a deep rumbling song which echoed

and re-echoed under the waters.” Sturgeon fell silent. Was that a faint

rumbling he felt along his centerline? Or just an echo of the ancient tale?

Sturgeon circled in the deep.

After a suitable pause, one of the catfish said, “ That’s a very

sad story. Did he ever come back?”

Sturgeon awoke from his musing.

“Well, the story actually goes on. They say the Great Sturgeon began

swimming round and round as she sang her doleful song. Round and round and

round. Faster and faster and faster. Day after day until the whole Bay was

spinning like a maelstrom. Then, in one great leap, she shot out of the water

– and flew away.”

“Wow,” both catfish cheered, clapping their pectorals.

“And that’s why Sturgeons leap,” Sturgeon said. “They

all jump as high as they can to show off for the ones they love. And maybe,

if they jump high enough, they will fly off with the Great Sturgeon.”

The catfish paddled in place, their eyes as big a saucers.

Then Sturgeon began humming a rumbling song to himself and started to swim

around the Catfish. Round and round. Faster and faster he swam. The catfish

were a bit alarmed, but Sturgeon was circling them so fast now they didn’t

dare try to escape. Then Sturgeon pointed his snout skyward, raced upward,

and crashed out through the shimmering surface. Sturgeon leaped way up in

the air. And there, hanging in the sky over the Bay was a gigantic flying

fish with great shining wings, whose roaring cry filled the air.

Sturgeon was struck dumb, and he landed on his side

with a bruising crash, splashing water twenty feet in the air. The catfish

scattered in panic. Sturgeon sank to the bottom in amazement.

It took quite a while for Sturgeon to regain

his senses. It was only then he realized that the niggling at the back of

his mind had been the rumbling of that Great Flying Sturgeon’s song.

And Sturgeon smiled. He had leaped high enough to see the Great Sturgeon at

home in the sky.

The big military C-5A continued to circle

Brunswick Naval Air Station and Merrymeeting Bay, doing touch-and-go

exercises. Sturgeon circled in the deep.

|