| ROSS LYLE MUIR was born in Beebe, Quebec, on December 27, 1921, and smuggled across the US border by Chinese Women. This would confuse later generations of biographers, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Young Ross was not baptised because his cousin got dipped instead, leading to a perennial confusion of names in the family. Such difficulties were not unusual among the Muirs, however. Ross’ father, George, married a George, and there were already too many Bryces to keep track. Ross’ older brother Bryce was particularly hard to follow. George called both boys Sonny. |

|

Ross’ father had grown up in the pool halls of Montreal, and Ross’s mother kept trying to get him out from behind the eight ball. This meant moving ahead of the rent collector, and the young family skedaddled from the granite cutting towns of Quebec into the Granite State. Ross’ sister Eileen was born in Claremont, New Hampshire. George only called her for supper. Not much is known of Ross’ years in Claremont, although the closure of the Opera House at that time may be attributed to unfair competition. It was the Claremont Opera Mark Twain referred to when he remarked he hadn’t heard such caterwauling since the orphanage burned. He may have confused the opera performance with the Muir family chorus. Ross has always been musical. |

When the Depression arrived in Northern New England, the Granite State was already prepared for it. The last big boom there had been in Civil War monuments, and rolling stones uphill was second nature to the locals. Their first nature will remain undisclosed, although George did say the neighbors were bent over so far they were stupid. When work dried up in Claremont, George chose to walk all the way across the state looking for employment, thus initiating the craze for walk-a-thons, bike-a-thons, rock-a-thons, dance-a-thons, and other absurd-a-thons to raise money for obscure purposes. He won the prize in Manchester, and the whole Muir kit kaboodled over to be near the Amoskeg. |

|

Manchester is now well known for the Hang Glider Festival, where avid sportsmen fling themselves into the air off Rock Rimmon. Ross has always been a little before his time. He tried this sport before there were hang gliders, and there’s a crease on his forehead to prove it. You should see the dent in Rock Rimmon. It may have been this aerial episode which initiated Ross’ stoical attitude, and his penchant for saying, “Ain’t that a kick in the head?” In those days you could walk out of Manchester and be in the country in a few minutes. This is undoubtedly where Ross learned his woodsy lore. As all his sons can attest, Ross likes nothing better than to camp out under a tree – preferably with Scotch and water. He can even manage without water. As George might say, you can lead a Scotsman to water, but you can’t make him drink it. |

|

In the Thirties, George and his Muir Tribe followed the work down the river valleys to Hartford, Connecticut. This is where Ross attended high school. Ah those innocent days. The only Herb Ross encountered at Hartford High was named Abrams, although he did manage to aquire a lifetime addiction to that one. A little know fact is that Ross was the star quarterback on Hartford High’s Latin Football Team. His most reknowned maneuver was the Hic, Hike, Hoax, which left the team from Boston Latin muttering in the pluperfect. Ross parlayed his liguistic prowess into a Latin scholarship to Colby College. |

|

Going to college in that distant era was quite unusual for a milltown boy, at least from Ross’ side of the tracks. But Ross had followed those big footsteps in the lobby and done well at Hartford High, and he’d also learned the lesson about the wheelbarrow. Not only had it taught the neighbor how to use his legs, it convinced Ross he never wanted to work with his hands – or at least his back. One season as a hod-carrier for a mason was enough. So he went to Maine to go to college. Of course Ross couldn’t afford to go to college full time, so he proceeded to alternate between laboring in the vinyards and sipping the wine of wisdom. He washed Carlton Brown’s windows with ammonia and newspaper, worked as a bobbin boy in the mills, and scooped ice cream for Wit Rummel, while he dodged the trains and soaked up English Literature and Economics at Colby. |

|

But a little education is a dangerous thing. Pretty soon Ross wasn’t to be trusted on the factory floor. When he pointed out to some workers who were up to their knees in a galvanizing dip that they might petition for better conditions, the boss took him into the front office. It’s always those damned intellectuals who cause trouble. Fortunately for the Managerial Class, war broke out in Europe. When Hitler proceeded to gobble up leibensraum and Uncle Sam sat on his hands, Ross went to Canada to enlist. But security was a bit tighter at the border crossing in Beebe, and Canada was loath to have him back. Some of you may recognize a family pattern here. When Ross pointed out his grandfather’s house to the border guard, the guard said “I’m paid to watch the front of this building,” and Ross went around back. |

|

Ross wanted to be in the Air Force, but Canada insisted their pilots be able to see, so he enlisted in the Manitoba Dragoons, and was sent to war in Saskatoon. This experience set such a high snow mark on Ross’s consciousness that retiring to Maine seemed tropical, but I’m preceding himself. Out on the frozen prairies the Dragoons separated the men from the boys, and the men were all about 6 foot 6. Except for Ross. Naturally he was put in charge. Ross’ job was to get his men to Halifax without them falling off the train. Luckily the liquor was so bad they couldn’t even walk. Having done such a sterling job of delivery, and considering all that Hic, Hike, Hoax, Corporal Muir was offered a chance to enter training for the officer corps. When his ship got to England, Ross was enrolled at Sandhurst, the Commonwealth’s West Point. |

|

Sandhurst was an eye-opener for Ross. Each young officer candidate had a personal batman to keep his boots blacked, and the senior officers rode up and down the stairs on their horses. Ross was moving rapidly up scale, and the extra pips on the shoulders of their jackets made the young colonials especially attractive to the native women. One young lass in particular caught Ross’s eye, Pamela Cooper, a London girl who worked as a tele operator by day, and danced up a storm by night–between Luftwaffa attacks. Pam’s father had run a family saddlery, catering to the American horse trade until the Depression killed the business, then he taugh himself to be a mason. Ross had sworn off carrying bricks for a living, but he fell like a ton for the mason’s daughter. |

|

Meanwhile Hilter was bombing the hell out of London, and R&R from Sandhurst meant dodging from pub to pub between bombing runs. Eventually Ross decided to put a stop to this, so he took an armored car into Holland and ended the war. Ross got back to England just in time to hitchhike to his wedding, then Pam hitched a ride with the Queen to the States. I’ve been told that Bryce Leigh crossed the ocean in the belly of a whale, but I think that’s folklore. I was also told he was found under a gooseberry bush, as many English children were, but I suspect that bush grew in Hartford General. |

|

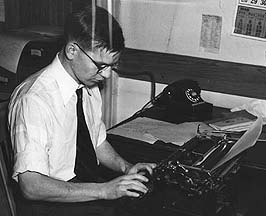

Ross and Pam and Leigh quickly moved on to Waterville, so Ross could complete his studies at Colby, but Leigh was 6 weeks old before they got there, so he will always be a Fromaway to the Maine natives. The Muirs moved in with Hope Bunker on Silver Street, and Ross took a job reporting for the Waterville Morning Sentinel, just down the block. He was there for such stories as Dewey beating Truman and the mayoral election of Ed Muskie. Ross acquired a taste for local politics, Hathaway shirts, and an interest in economics. After all he now had a family to feed. |

|

Some of you may remember those Halcyon days, when America had saved the world, and the whole shebang was our oyster. Ross figured the best oysters were in New York City, so he packed up the tribe and proceeded thence. They settled into luxurious accomodations on North Brother Island in the East River, and shared a ferry with their neighbors on Riker’s Island. To this day the sight of manacles makes me feel to home. As does the smell of turpentine and oil paint, thanks to sharing a bedroom with Herb. Ross enrolled in a Masters program in English at Columbia, and began juggling participles in Rockefeller Center. You may still notice the impact his linguistic sensibility had on Time Magazine. Their punning is so Lucid. |

|

But the big story in New York has always been downtown, and Ross was soon reporting about the traffic on Money River. Malcom Forbes had a fledgling magazine designed to inflate later balloons and buy motorcycles, and Ross took an editorial position there. Hunched over a Remington. The family moved to New Jersey so Ross could commute with different criminals – in pin stripes this time. As the rising tide of affluence lifted all boats, Ross and family navigated from East Patterson to Ridgewood, and then to Glen Rock where he purchased their first house, and Pam painted the walls purple. |

|

Ross had been covering corporate news at Forbes, and in the early Sixties he took the pieces of silver and went to work as PR director for Ruberiod Corporation. This included such perks as all the asbestos you could take home for your children, and bags of shingle gravel to use on model railroad layouts. Meanwhile Pam started flying airplanes, and she and Bryce Leigh caught an incurable case of Maineitis from spending their summers at Owls Head. Ross would commute to the Head on summer weekends from New York in the family Ford, arriving in early hours of Saturday morning and sleeping in the sun until he looked like a lobster. The Saturday morning he tried pole-vaulting on his drive shaft down Route One may have been the last time driving all night was any fun |

|

Bryce Leigh was having so much fun he got sent away to school in Massachusettes, the cruelest thing you can do to a Mainer, but not so bad if you live in Jersey. About that time Ross went to work for Tri-Continental Corporation, to pay for all the plane rides and fancy books. It must have been a pretty good job, because he stayed there for more than 20 years. I was never quite sure what he did, except it involved getting a lot of liquor from printers, and a season of high craziness called Annual Report Time. Ross got involved with the wrong sort in Glen Rock, and, made giddy by the enthusiasm surrounding John Kennedy, he actually ran for town office as a Democrat! In Bergen County! Obviously he wasn’t elected, which may have been the saving of American politics. |

| Then the Sixties happened, and the whole world went nuts. It had something to do with an invasion of Beatles and some place in Southeast Asia. Kennedy was shot, Bryce Leigh made it through Andover by the skin of his teeth, and Pam flew off with her flight instructor. Ross moved into Manhattan and Bryce Leigh joined him there, taking a job at the Journal-American. It was very strange going on double dates with your father. Fortunately we both fell in love. In my case it was just dumb luck, but Ross had professional help. Carolyn Hunter was a executive search professional, and she found the right man. Ross found the woman he’d always been looking for. They were married by Norman Vincent Peale – wasn’t it? Things certainly got better and better. |

|

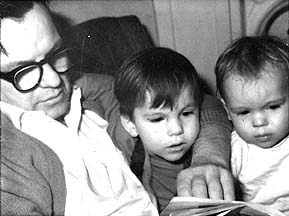

Ross and Carolyn soon had two bouncing boys and were happy as apples in the Oranges. Carolyn retired from the headhunting game, and Ross kept sending out press releases. Carolyn began doing church work in Newark, which may be why Ross bought them a house in Basking Ridge. This was an especially astute choice, as Ross’ new commute gave him time to read every last word in the morning TIMES. He also became an expert in newsprint origami, a prerequisite for commuters on the Erie-Lackawana. There was nary a lack or a wanna in Basking Ridge, and Lyle and Ian grew up well-loved and well-educated. Ian may have thought there were too many … rules, but he knew how to play by them. Lyle, of course, learned how to win by them. Both boys went to Lawrenceville, which they shouldn’t be embarrassed about – really. |

| By the time Lyle and Ian were off to Colby and Bates, Ross realized he better find a way to coin money – so he invented the Money Fund., and sold the idea to Lehman Brothers. There‘s a great deal of honor among thieves, especially rich ones, and there are no more honorable dealers than bankers. As Willy said, “That’s where the money is,” and Ross managed to deal himself enough honors to educate four children at private colleges – Lyle and Ian included. But the call of the wild North began beckoning Ross. Maybe it was nostalgia for all that snow in Saskatchewan, or the evocative sights and sounds in Lewiston. Perhaps the lure of Route One was simply too strong to fight. Ross cashed in his chips at Lazard Frere and left Rockefeller Center for good, headed downeast. |

|

Carolyn looked at 175 houses before she found the right one, in Litchfield – the only house in Maine with a dry basement and enough walls for their paintings. While she was searching, Ross re-established contact with his Colby classmates, and personally saw to the installation on campus of a bronze mule. He also negotiated the building of a wing on the Colby Art Gallery dedicated to the paintings of Alex Katz. In fact Ross has become quite a connoiseur of modern art, and has taken to wearing shirts designed by Fred Lynch. Or was that Merrill? Finally – Ross’s biggest coup since retirement was making contact with his long lost Colby classmate Barney Bailey. I know Barney would want to join us today in celebrating this moment, but, unfortunately, Barney is suffering from wounds received chasing a nurse in his wheelchair. No one is really sure if she pushed him downstairs. |

| So for Barney, and all of Ross’s other friends, I’d like to salute Colonel Muir on the occasion of his almost 80th, and to wish him good health – and long life. |