Sagadahoc Stories #74: 1/10/99

Winter Roads

Last week's snow storm went out as frozen rain, leaving a thick

crust of glaze everywhere. The slop quit after midnight, and I

got up with the light to survey the damage. Not a patch on last

year's big ice, but slick and glittering enough to get your attention.

Evergreens bowed in supplication. I chopped the Owl out and got

him shuddering in time to head off to court. Jury duty. It never

snows but it rains. And freezes.

|

The world was spectacular in the morning light, bare trees all

illuminated, fields asparkle. I was glad to have been rousted

out, but hoped I might get home before the plunging temps made

our dooryard a concrete installation. Faint hope. I made the cut,

and didn't get released until after dark. Mercury out of sight. |

Worse yet I'd promised to milk the Torberts' goat, but the Yard

traffic was so bad in Bath that I sat in a stalled line of yardbirds

downtown for half an hour, trying to get across the bridge. Pretty

exciting for a country boy. I finally gave up, hung a U-ey, and

went the long way round to Whitefield.

| This was my first time ever milking anything, and I approached

Helena cautiously, speaking calm words with false assurance. She

looked as dubious as I felt, but pretended I knew what I was doing.

Got up on her milking stand and submitted to my ignorance. I couldn't

get her to let down at first, and had panicked visions of infected

udders, miserable hours of goat angst, desperate phone calls to

Oklahoma. But she started to squirt, and before long I was thinking

about striped overalls and straw hats. Farmer Bryce. I like it. |

|

Next morning I was hooked. The long drive across an icy predawn,

the wakeup slap of subzero air, the comfortable sense of mutual

aid, exchanging udder relief for a quart of fresh milk. Lying

your head against rough fur and hearing a goat's belly grumble.

I can feel the pull of ritual husbandry. I'm not sure how many

of those things I'd want to pull each day, though.

|

I was back on the road to Bowdoinham at dawn, cranked up and camera

loaded. I was determined to get at least one picture of backlit

ice, and roamed the eastern districts as the sun lifted. Tough

trick. I filled a chip with images, only to find later they were

mostly throw-aways. In the process I encountered other rogues

enjoying the spectacle.

|

Piers was sipping on some java when I pulled into his dooryard,

hoping to get a shot of Chops across the bay from his windswept

perch. He waved me in and opened up another way of seeing the

town. He's been arrowhead hunting the past couple years, and brought

out his flaked finds to show me.

| There's a tribe of pothunters around here, and the evidence of

Indian settlement is thick on the ground. It wasn't called Merrymeeting

Bay for nothing. A seasonal hunting resort for many tribes at

the time of contact, the estuary had been a favored spot down

through the archeological record. Only the PaleoIndians are under-represented,

and that may be because sea level was considerably lower then,

and the sites are now drowned. Ten thousand years ago Chops was

a waterfall. |

|

By the 18th century many of the villages had been decimated by

European diseases, but there was still a large Abnaki town on

the tip of Swan Island. (Kenneth Roberts in his novel Arundel

has Aaron Burr fall in love with its lady sachem.) Now the island,

splitting the Kennebec's entrance into the bay, is a state reserve,

and frequent resort of amateur archeologists.

Talking to Piers my view of the bay is transformed. An imagined

map of Indian towns springs up, and the waters are teeming with

sturgeon and ducks. Outside the harsh sun bounces on glare ice,

but next to a warm stove we're back a couple of eons holding a

flaked scraper in a summer camp. Some of the artifacts have a

charge when I touch them. I get a distinct sense of heavy hands

and mute intentions. Voices strangled in dirt. As though a broken

spear point was trying to speak into my holding. I put it down

carefully.

|

There are as many towns here as ways of seeing it. Since I've

been drawing this place, it's been the skeletal forms of things

that have been my town. The habits of trees, the frame of buildings,

the opening of lines of sight. Writing about it, the town fills

up with personalities, half-told tales. Now the thought of shards

and flakes gives the place a depth of time that's vertiginous.

I staggered out of Piers' uncertain of my footing.

|

| The boys on the Abby were into the fish, and I helped Dr. Bob

work his lines for a spell. He's using double-ganged lines, and

when the smelt are hitting it gets too busy to talk in his camp.

Almost spoils the fun. Next door Sam the Restaurateur was fishing

with Brent, and we all commiserated on the wages of sin. How we'd

all stumbled out of the 70s onto non-institutional roads, lived

hand-to-mouth, and now, in our 50s, were surprised to have bank

accounts. Sam, in fact, has made a spectacular success of his

Portland restaurant, and is arguably this state's foremost chef.

He carried off their catch to serve that evening. |

|

Chubby on Ice

|

I made it to Brooklyn after noon, still charged up, downloaded

my pictures, and managed to salvage one good shot for a painting.

Spent the rest of the day in The Eagles sketching and carving

as the light poured into the big windows. Peggy cozy in the house,

ashwood burning in the cookstove, fresh fish for dinner. One of

those perfect days. |

Jim's hadn't been so good. His daughter's wedding in Tulsa had

been an emotional event, and the flight back to Manchester was

on time, but Jim had left his car at the airport with an almost

empty gas tank, and the sub-zeros had seized its filler pipe.

When he tried to put gas in, only a dribble would go. He went

from station to station doling in a cupful at a time, until he

got to Yarmouth, where it wouldn't take any more. Our phone rang

at midnight.

It felt just right to take the energy of such a day and pass it

along. I retrieved Jim, drove home, and gave him the Owl until

we figured out the next step. When he got to Whitefield the message

was waiting that his mother had died. About the time his car broke

down. A very hard season. Weddings and funerals. Hospices and

recovery rooms. The backsides of gas stations. This winter has

been full of transformations, and new roads.

(Next day we returned to the dead car. Jim ran on fumes to a nearby

carwash, thawed the fillpipe with hot water, gassed up and was

back on the highway. Punchy, but automotive.)

| Wednesday I tried skiing the river, and it was deadly. Barely

enough traction in the good places, and wicked slick between.

CC and I slipslided up to the second middleground to see if anyone

was fishing there yet, and found only one cold camp dripping icicles.

By then my inner thighs were aching, and we let her skid for back. |

|

Amazing how quick the ice makes. A few nights in the deep freeze,

and the ice is booming. A bit disconcerting how quickly you adjust

to the ice roads, too. One day you're poking around the edges,

spooked by every clunk and crackle, the next you're out gliding

down the channel as though it were asphalt. The shanty boys all

report 8 inches of ice or better, but that doesn't say anything

about the thin spots, and with a snow skin over all who knows

where they are.

|

CC always used to follow Bagel onto the river. He seemed to have

a sixth sense, or maybe no sense, as he usually took at least

one plunge each winter. Now she waits for me to go on ice, and

trots right beside me. I had to jab my poles in at each stride,

and shoulder my way along. But the crystal crust was too crunchy

for skating. Snowshoe weather.

|

Thursday I buckled on the big webs and tromped out into the woods.

CC skittering along on the crust, breaking though up to her belly

every dozen steps. In the still air the noise of snowshoes crunching

through glaze is jarring. Maybe that's why they were called rackets.

On river ice the flutter of the shoe behind you starts a shuffle

rhythm, and I find I'm dancing to the beat.

Ideal shoeing. Absolutely miserable for anything else, this kind

of surface makes everywhere accessible by snowshoe. It's all road,

and I gallop off in all directions. A biting norther is lifting

what little powder got dropped in the night, and I shape my course

to stay in the lees. Suddenly there's another map for this terrain.

The Indian settlements followed rivers, because they were the

roads. The primeval forest was called "trackless", and "impenetrable",

by the "discoverers." My notion of old woods as open stands of

soaring trees is typically European, where centuries of gleaning

kept down the undergrowth. Even though the Indians set deer fires

to open the woods, the descriptions of early travelers suggests

that the American wilderness was more like the strangled woods

of Maine islands than the groomed parks of Great Britain. The

choked third growth out back here may be more like the original

woods than the imagined cathedral forest. It was in the winter

that the Indians went upcountry, when they could travel the snowroads

on rackets.

| Post contact settlement moved up out of the swamps and lowlands,

then away from the rivers, as highroads were opened and waterpower

lost its edge. Hard to believe there were only a few Indian paths

and buffalo trails at contact. Reading Colonial history it's almost

impossible to imagine how a few forts on the rare roads, or at

the crucial water narrows and crossings, could command North America.

The idea of universal mobility is now so ingrained that a time

when there was only one way to Pittsburgh seems impossible. But

when you put on snowshoes, and discover you've been confined to

familiar ways in your own neighborhood, you realize how much our

mental maps are the creatures of habit, and conditioned by environment.

Riding the crust out of the wind I discovered that a bend of the

river is only a stones-throw from one of my haunts, and I never

knew it. The drowned jungle in between barred that knowledge.

The old road went around. |

|

Snowmobiles have transformed the winter landscape, of course,

changing land use patterns faster than you can say "comp planning."

Thursday I got hailed by a neighbor I've never spoken to because

my shoepath crossed a ridge opposite her window. All the angles

were different. Sudden changes in weather rearrange our mental

maps. The roads we know don't work as well, or new ways of seeing

the world change our direction. Now we've had another storm, culminating

in a day of rain. If it stays cold, we may break out the skates.

The rivers will be the best roads again

Meanwhile the local convalescents are stepping cautiously on ice.

Peggy is making a short peregrination along Wallentine's road

each day, and Annie is out checking on her tractors. She and Russell

set off Christmas week in her tractor-trailer to haul a load to

Texas, but she keeled over in the cab somewhere in Pennsylvania.

Russell thought she was a goner. Couldn't find a pulse. Grabbed

the cell and dialed 911. The ambulance was there in minutes. Says

it was the wildest ride he ever had, and he used to race stocks.

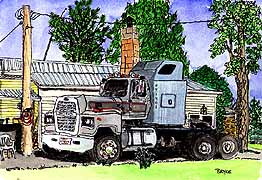

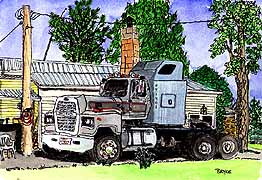

Annie's Ford

|

"Must have done something to the suspension of those converted

one tons," he asserted. "They corner like nothing you'd believe.

If she'd've been up front she'd've had a heart attack."

As it was Annie'd had a stroke, but you can't keep her down. Chico

drove to the hospital and brought her home. No paralysis. No slurring.

Annie has a tongue like a rasp, and it can still tear a stripe

off you. Glad to hear it. Ought to be declared a town treasure. |

Fowler, who lives next door, says it was snowing when they set

off, and she was wearing her usual T-shirt, shorts, and flipflops.

Once she takes up residence in the rig, she doesn't stir until

they're back. She was wearing peddle-pushers the day I dropped

in, though, and was full of plans. Talked about selling the trucks

and buying a mobile home. Maybe one with two bedrooms, and a vanity

plate says "WHOREHOUSE." Always get good parking in the truck

stops.

|

"How old ARE you," I asked.

"78 and never been kissed," she said, standing up with her lips

puckered.

I obliged. "There," she sighed. "Finally been kissed."

This morning Annie was out in her shorts, again, in the sub-freezing,

poking at the tractor with a cane.

"What are you doing out half naked," I yelled.

"I got my underwear on," she defended herself. |

BFI

|

|

We may not know the next road, but we're on the mend. |