Sagadahoc Stories #85: 3/29/99

Parts List

| Signs and portents continue. Mr. Mann reports that turkey love

commenced the first day of Spring, right on schedule. The big

tom that's been tending his harem at the feeder behind the Mann

house blushed his wattles on the equinox, and fanned his tail

at the hens. They got all excited, neck bobbed and gabbled enthusiastic,

then paraded after him into the woods. |

Kay Gray Photo

|

|

I followed CC into the puckerbrush one midday, sporting my yellow

rubber boots and a pair of shades, looking for some seasonal excitement

myself. The surface frost has turned to mush where the sun has

touched it, but down in the hollows you still crunch through frozen

crust, sideslide the slopes, and tip-toe over ice bridges in the

swamps. A splay-legged hobble with your ass hung low is the only

way to stay upright. Spring Shuffle in the Maine woods. |

| Rain and sun have dissolved the snow under the trees, but out

on the trails, where it lay deeper and more compacted, granular

masses of old winter still swallow your boots. You can see white

highways winding through the dark distance between the trees.

A new woods landscape where contrast is the subject, and old duff

the dominant tone. |

|

|

The last persistent beech leaves ocre and rattle the air, waiting

for new buds to unhinge them. The rest of us are pretty unhinged

already. A few days in the 40s and us seasonal shut-ins are out

kicking the ice clumps, setting small fires, and otherwise celebrating.

Every surface is wonderfully dirty. Old bog ice is coated in silt,

dead leaves have a gritty rind, all the detritus of winter lies

scattered on top. You realize how old settlements can disappear

under layers of dirt in a few years. CC was in glory up to her

ears. |

| We rousted out Mr. Mann who was finicking over his romantic study

of Barbie and the Crash Test Dummy. I'm constantly astonished

at how David can labor on a watercolor for weeks, lifting and

washing, pushing depths in and pulling forms out. If I belabor

a watercolor it turns to muck immediately, but he can polish it

to a glow. This still-life is one of his current projects, and

I was delighted to see that he was using stills on a video monitor

to work from, in addition to the actual objects. The VCR image

captures the light of a particular instant, and lets him zoom

in on details. How apt for Barbie to be studied via video. |

Barbie with Dummy

|

River Ice

|

CC led us down to the river, and leaped from beached flow to flow.

We didn't join her for a ritual immersion, and tried to dodge

her shaking it off. The tide was still wheeling loose cakes and

pans upriver, and the marginal flats had rows of fractured white

trimming the scene. Close up, the trees looked dormant, but a

wide-angle view showed the maples and oaks tinged red with buds.

You might call a painting of late March "Bleached Beige and Buds." |

When CC and I got home, my blood was up, and I started pacing

out where this boat is going to arise. A sudden cry startled the

air above me. A haunting musical note. Half honk, half scream.

Ducking and twisting my neck, there was a pair of courting eagles

cavorting over my head, tumbling through an aerobatic arabesque.

In a flurry of wingbeats they were gone and I was breathless with

joy. That eldritch call, the great beating of wings, and the immensity

of the birds close up. Magic. Initiation fit for an ark.

|

|

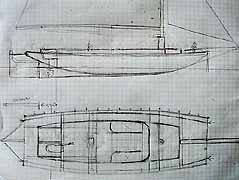

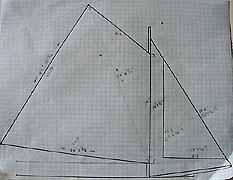

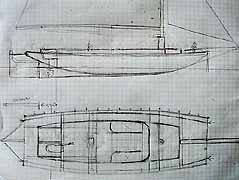

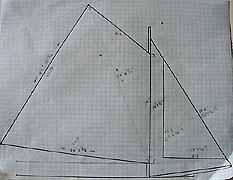

With that motivation I began the boatbuilding process in earnest,

which means making a host of small decisions. Although the basic

hull shape of this vessel is clear, a curvilinear box, I have

to come to some understanding of the construction details before

I can gather materials. Building a boat is both like and unlike

conjuring a sculpture. Instead of marshaling images of subjects

and animals, then making a rough sketch, I steep myself in boat

plans and photos, then pencil out a crude set of lines on graph

paper. Both creations start with envisioning, but where one form

mutates with the materials and evolves as the image is realized,

the other is built on a rigid skeleton, and the essential expression

is defined before the first timber is bent.

Right now there's a bunch of conundra to untangle. How will she

be sparred and rigged? What kind of rudder? How steered? How will

I mount the outboard? Centerboard or lee-boards? Full length skeg?

Stowage and hatches? Sun shelter and a swim ladder for Peggy?

Seating? Some of these determinations will affect basic framing

and hull construction. Others are superficial details, but it's

better to thrash out as much as you can before you start setting

up, lest you overlook a crucial ingredient. This is seat of the

pants marine architecture, so I have to put a sheen on my britches

first.

But there's the timing factor, too. If this baby is going to splash

in before the sun gets too high, I have to line up my materials

so they're handy when I need them. For starters I need a strongback

to build on and one-by to puzzle molds out of. Then I'll need

frame stock, and planking, and fasteners. Capt. Ken has been a

great source of practical advice, even though he thinks I'm nuts

to be building a scow, while the boys at the restaurant have been

egging me on, and debating details. But at some point I have to

fix on a plan and get wheels turning.

In the end I came down to two closely related hull shapes, both

recorded by Howard Chapelle, the great marine historian, in the

1930s. One, constructed by a builder from Bath, has finer lines

than the other, taken off a hulk in Freeport, of unknown provenance.

The first looks sweeter to my eye, but I'm wary of that instinct.

When I built Sharpie I stretched her molds to make her look finer

to me, and run faster under power, but it resulted in a very tender

sailer. This time I intend to spread a lot more canvas in proportion

to her hull size, and I'm leery of making her too lean. The fatter

boat would be 8 foot at the beam and 24 long. The lean one would

be nearer 6 in a 24. I measured up enough materials for the beamier

beast, just in case.

Reader (After Barlach)

|

Measuring old plans, converting to the size you want, figuring

up scantlings and fastenings is nervous work for me, as I'm constitutionally

innumerate. I don't count so good, either. I made a rough calc,

though, and went shopping.

|

First stop was at Morse's mill in Winnegance. Doing all this reading

about the history of the Sagadahoc it felt right to be smelling

fresh-sawn lumber down along the Kennebec, where they've been

playing this game for 300+ years. You get disabused of your romanticism

real quick at Morse's, though. Wander in with a scribbled parts

list and a bit of uncertainty and you'll get a tongue-lashing

for being an irritating nuisance.

|

I'd done business there before, however, and expected to be embarrassed

about my ignorance as part of the routine. Good to be reminded

you don't know diddly. After Morse decided to bother with me,

we eyeballed some oak logs. He asked, "Red or white?" and I said

I'd always like white if I could get it, and asked if it wasn't

a bad idea to mix the two.

"I don't know as it makes a difference," he grumbled.

|

Diddly (After Barlach)

|

Fact is, Fowler once showed me how you can blow smoke through

a length of red oak, because of its open pores, while you can't

with white. Which may help explain why the red oak in Sharpie

went punky so soon. But I wasn't about to make demands at Morse's.

If he wanted to saw white oak for me, he would, and otherwise

I was just blowing smoke. Morse took me around the end of a pile

and pointed out a stick of white oak, which had a lovely twitch

in the end that would suit the skeg to perfection. I said so,

and he grunted.

Monks (After Barlach)

|

We sat on a pile of lumber and he sketched on a board, asked me

about construction details, copied my parts list onto a slip of

paper.

"When do you want this?"

"At your convenience. I hope to be setting molds by the first."

"Well, maybe next week. I've got a delivery up your way anyhow." |

I didn't even think to ask about price, but I know it'll be the

going rate, and the measure will be just right. I could have gotten

oak up here, but it would be red, and without the twitch. So I've

ordered framing in Winnegance. Five-quarter live edge, two-sided

to one inch, and finished four inch for the skeg and bowsprit.

Saturday awoke mild and sunny, and the whole town spilled out

into the Springshine. Harvey came up and helped me get Ebba running.

He deduced a weak spark and maybe a soft accelerator pump in the

carb, but she fired when he advanced the spark, and I managed

to keep her awake all day. He went up to Messers and got a distributor

with an electronic ignition on it to try and boost the juice,

but we didn't get it cleaned and installed before dark, so much

was going on.

|

|

|

I learned that it's hard to change you automotive habits. All

those slant six Chryslers I rodded around in could be goosed into

life by pumping the throttle vigorously, so I tend to work the

gas like mad when cranking a cold beast. With the big 4-barrel

on this 283 a little pumping goes a long way. Too far, in fact.

She'll start without any goosing, if at all. My ankle was shaking

with anticipation each time I started her Saturday, and I had

to talk to it like an eager pup. Maybe I'll learn to be a Chevyite

yet. |

| I ran into Eric the woodman at the gas station. He was just finishing

a logging trick and said he'd be home at the mill later in the

afternoon, so I rolled the red lady out the Millay Road and down

201 as the sun declined. When I got there one of the Temples was

yarning in the yard, and I got an extended run-down on the old

buildings in town and their confused ownership, new insurance

requirements for the Knights of Pythias Hall, and the history

of local fire engines. The fire department has two old hand pumpers

stored away, and they've been talking about asking me to do paintings

of them, he said. I said I'd be delighted. Apparently the old

Phoenix is one of only two still in existence. He told me when

he was a boy the department used to take the other one to musters

and compete against teams from all over the state. The crew from

Rockland trained like athletes for the musters, and always took

home the pumping prizes. |

Pulp Loader

|

I took home a truckload of 6X6s and 1X4s for a strongback and

molds, and made an arrangement to pick over some clear pine to

run through Eric's planer to make plank this week. Looks like

I've got my lumber lined up. I may have found a name, too. In

a history of Bath written in 1842 I read that the Indians called

Merrymeeting Bay "QUABACOOK". Maybe a good name for this square-toed

frigate who'll dance on the Bay.

Model A

|

Spring fever has everyone turned upside down. They closed the

Town Landing for four days this week to start building an apartment

into the big lumber room upstairs, and do spring cleaning in the

restaurant. It took Jeanine the full rigmarole to get planning

approval for the apartment. Not only was she required to submit

detailed documentation of plans, septic use, flood plain siting,

and letters of OK from the abutters, but she had to endure an

examination before the planning board, who have been hostile to

restaurant renovations in the past. Back when Bruce and Judy ran

the place the board slapped down all the proposed renovations

they asked for. Jeanine isn't quite as hair-trigger as Bruce,

though, and hung in there through the whole charade. |

| You could hardly argue that it isn't a residential area, with

three out of six abutters being residences, and you could hardly

argue increased parking problems with the restaurant parking lots

empty all night. Angie and her man, Eric the artist, are going

to live there as Angie takes over the business. You'd think the

planning board would like to see a vital business thrive, but

Jeanine was asked if "a family" might live there, as if that wasn't

quite proper. |

|

|

She got the go-ahead, anyhow, and now a new suspended floor has

been spliced in upstairs, new tiles have been laid in the restaurant,

and the whole place sparkles. It was mobbed all day and evening

on Friday, after they reopened, and we soaked up a bunch of chowder

in celebration.

|

| It's been a treat to watch the changing of the guard at the Town

Landing. As Jeanine has relinquished day to day management to

Angie, she and Dianne have begun to look more relaxed, taken some

real time off. Angie and Allie, Jeanine's girls, have been running

the day shift Monday to Friday, and keeping the regulars happy,

while mom comes back on the weekend to spell them. After Short-order

Bob handed in his spatula they hired Christine, to wait table,

and now Eric is working the grill as well. What with Allie's little

boy Aaron spinning on the stools, and Eric there for Angie, the

restaurant feels like a home. |

|

|

Jeanine says it's hard to let go of it. The place has been her

baby for nine years. But she brought it up good, and what could

be better than turning it over to young lovers, in the Spring?

There were jonquils at every table when the doors reopened. |