Thinking Backwards

The great ball court at Chichen-Itza is quiet in the hot sun.

The clicking of Japanese cameras, the clapping of tour guides

raising an echo, and the flicker of an iguana moving in the rubble,

barely stirs the millennial silence. High up on the two long facing

walls, vertical stone rings stand out at right angles from the

limestone facades. In the ritual games, teams contended to kick

a large, hard rubber ball through these hoops, they say. The losers

were ceremonially killed. Or was it the winners?

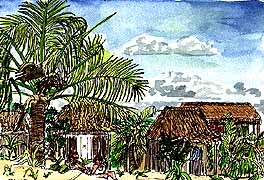

Peggy Sketch

Tulum

For all our archeology, we don't know much about Mayan civilization,

really. Chichen-Itza flourished around the year 1000AD, but most

of the Mayan cities were swallowed in jungle before the second

millennium was barely started. There are still Mayan Indians throughout

the Yucatan, but waves of conquest have silenced history. The

hawkers selling ersatz artifacts at the gate are only interested

in dollars.

We went down to the Yucatan over Christmas to meet Seth, after

his sojourn in Belize, thinking that standing among thousand year

old ruins might ease us of the daily complaint. Seth had his hammock

hung in a cabana on the beach at Tulum, within sight of the Mayan

temple ruins there. He'd gotten us a room in a low rent hotel

on the main drag, three pot-holed miles from the sand.

Reverse View

Seth & Peggy on Beach

The scene on the beach was pagan enough. Scads of world youth

with their clothes off, beating drums, and snorkeling on a dying

reef. The longest barrier reef in the hemisphere. Seth had been

diving on it farther south with his field ecology team, and was

saddened by the unraveling of the threads. Now he was soaking

the bennies on these coral sands, recuperating with a broken collarbone

after an incident in a bar in Punta Gorda. Peggy and I felt like

ancient history among the topless babes and athletic dudes.

I'd expected to get an intuitive charge in the old sacred quadrants.

Pursuing a scheme to sculpt main currents in the American mythos,

I hoped to touch the sources of the Corn Peoples. The earliest

maize material was found in the Tehuacan Valley, dating back to

5500BC, and it was the Mayans who selectively bred corn until

it could support a civilization. Maybe the corn carriers left

traces among these ruins. If so, I couldn't sense them. Even in

the press of gawking tourists, my strongest impression was of

emptiness. A hollow silence from which the spirit had flown.

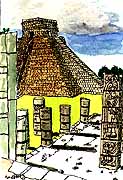

Hotel Italiano

Chichen-Itza

At Chichen-Itza Seth lay down in the sun on the grand plaza and

slept, while Peggy sketched hieroglyphs, and I found a perch from

which to paint the great pyramid. A bit of shade, a place to sit,

a piece of foreground. I was soon surrounded by a gaggle of Italian

tourists watching the hand-eye exercise. Do all the tourists wonder,

as I do, why we make these pilgrimages? Were they looking over

my shoulder for an answer? What does it mean, this manhill in

the jungle? When Seth woke, he reported having weird dreams.

History is a weird dream. A thousand years ago men were piling

up monuments to the great mystery. Peggy and I have spent time

at some of them in recent years. For seven months in 1990 we lived

in the medieval city of Norwich, thanks to a Fulbright teacher

exchange. Living in what was once a weaver's cottage, over an

old Saxon well. Every day I walked the city precincts trying to

dowse ley lines, and intuit the old processional way from the

cathedral. Where did the city patron, George, pursue the dragon

on his Saint's Day? Even in the hubbub of a modern English city,

there are openings into other times, although sorting intuitions

from imaginings is a fool's errand. Just the job for me.

Norwich Cathedral

Walking, photographing, drawing, reading Grail legends and Arthurian

romances in the cathedral close, I began to sense an holistic,

geomantic landscape. I kept encountering the same itinerant painter,

invariably setup in the very vantage I had followed a trace to.

I finally asked him, half joking, "Are you painting the ley lines?"

Without a blink, he replied, "That's where all the good views

are." But they were just glimpses for me, and I wondered what

it was that had me perusing this old ground, with an eye turned

inward. Some years later I discovered that my grandmother's people,

named George, who arrived in New England in the early 1700s, originally

came from Norwich. Maybe it was a genetic memory I was chasing.

The memory I carried away from Norwich was of a soaring cathedral,

aligned with the light, set in an invisible web which under-weaves

the landscape. Although the Christian symbolism rose up to exalt

a celestial deity, man risen to God, there were still Greenmen

on the bosses, pagan vestiges on the facade. The whole ethos of

sacred space aligned with the spirit of place permeated the old

city. While the troubadours sang of romantic love, and a grail

quest, the peasants still paraded Old Snap, and dropped wishes

in the well.

St. Ethelbert's Gate

Cloisters

The cut Caen stone for Norwich Cathedral was barged from France

to this muddy meadow by the Wensum. One day I twitted the workmen

doing restoration work in the cloisters. "Aren't you afraid that

you'll mess up the symbolism and something horrible will happen?"

A young mason came down from where he was repainting a boss, and

said, "My father was a mason, and his before him, and so on. They're

all buried over there." He pointed into the cloister green. "And

they knew a trick or two. You ever think about what this cathedral

is built on?" I said, no, but it looked like clay. "Ever know

a building to sit square on clay, for even a few years, let alone

a thousand?" I had to admit it wasn't likely. "Ah," he said, lifting

a finger, "First they laid down a bed of feathers, so the building

could fly." His partner exploded in laughter.

We've forgotten the little magics, and much of the vulgar symbolism

in the carved details. Scholars are now rediscovering a sacred

geometry architected into the great cathedrals. In our ascent

to ever more rarified abstractions we forget how four-square and

down to earth people once were.

Greenman Boss

The Owl at Cahokia

Back on our own turf, Peggy and I took a sabbatical drive around

this country in 1996-97, chasing American history and a sense

of symbolic geography. More by chance than design we encountered

the Mississippian culture. The great earthen pyramid builders

of the first millennium. We stumbled upon Cahokia, that extraordinary

earthwork metropolis in the American Bottom.

Isn't it astonishing that we never learned about Cahokia in US

History, or AmerIndian Ethnology? A thousand years ago, in what

is now East St. Louis, there was an Indian civilization centered

on a city of 20,000, which influenced all the peoples of the American

heartland. From Florida to Oklahoma, from the Gulf to the Great

Lakes, artifacts have revealed a Mississippian culture in full

flower at 1000AD. We made pilgrimage to sites all over the South

and Mid-West. Our lessons had taught us the American Indians were

nomadic hunter gatherers without pots to piss in. What a convenient

myth for a manifest destiny.

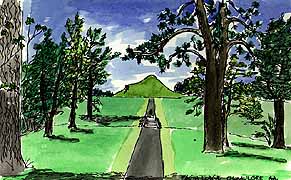

Bryce's Cahokia

Peggy's Cahokia

The big "mound" at Cahokia covers 14 acres, and is 100 feet tall.

Around it are the remains of more than 100 other earthworks, slowly

giving up their secrets to archeologists. Although early travelers

reported on the numerous mounds they saw near the rivers, the

earthworks were treated more as nuisance anomalies, to be bulldozed

away and forgotten. Even though DeSoto had wintered in one of

the last Mississippian towns, at Natchez, it was more convenient

to forget. To call the natives savages, and ignore their works.

Now archeologists believe the works at Cahokia were aligned to

the stars, and the seasonal turnings of the sun. A bird-man and

a solar chief head the iconography. An immense plaza was leveled

with clay for ritual games of "chunkey", where spears were thrown

at rolling disks of stone. Celestial alignments were marked out

in huge "woodhenges", and a variety of ceremonial earthworks were

engineered (with sophisticated interior drainage), over a relatively

brief span of years.

Earth Lodge at Ocmulgee, Georgia

The Mississippian culture was founded on corn, a tropical grain,

selected for increasing cold resistance as it was passed along

from people to people. Corn transformed nomadic North America,

and the first Europeans settled on corn fields their imported

diseases had depopulated. By then Cahokia had been abandoned.

The Mississippians, like the Mayans, had become little peoples

again. Dispersed by cultural upheavals we can only surmise upon.

Ecological collapse, due to cooling temperatures, rising water

levels, or soil exhaustion? Conquest by more warlike hunter gathers?

Indigenous disease? Or merely a cultural evolution back to dispersed,

less authoritarian, communities? We don't know.

We do know that a thousand years ago peoples in Mexico and the

American Bottom and East Anglia were celebrating the connection

between the mundane and the divine with stupendous works. The

mortared rubble pyramids of the Maya, faced with limestone carvings,

now show their crumbling interiors. Those "mounds" that are left

in East St. Louis, are covered with grass and trees. And the carvings

on Norwich Cathedral are dissolving in the acid rain. But they

are still turned to a sacred geography. Still point to the stars

and solstices.

Acid Rain

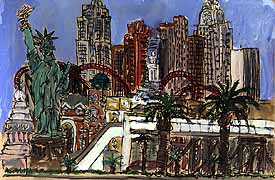

NY,NY at Vegas

We're putting up some pretty remarkable monuments, ourselves.

How long they'll last, is a question, of course. We may find out

about ecological disaster, or cultural implosion. But it's a rare

edifice these days, which symbolizes the divine in man, or the

link between earth and sky. The higher religions, which look for

a light within, seem to have forsaken the light without. Man is

reduced to happenstance in a blind cosmos, or elevated beyond

his material being. There is no sacred landscape. If we face a

house south, it's for solar tempering. We don't frame a window

to the east for rebirth, or one to the west for our soul's passage.

The artisans of 1000AD, at Chichen-Itza, and Cahokia, and Norwich,

weren't glorifying their individual artistry. They were each holding

up a small mirror, so man could see himself in the cosmos, and

the cosmos could show itself in man. Every artist was steeped

in a language of sacred symbols everyone understood. A culture's

tales were told in an inner vocabulary. We can barely begin to

think that way.

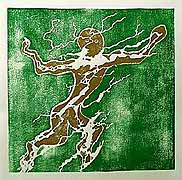

Dancing Sagadahoc

But it's worth a try. This place we live, by Merrymeeting Bay,

is at a confluence of many waters. Rivers that rise in the White

Mountains flow down the Androscoggin, to meet the waters from

Moosehead, and the central uplands of Maine, which run in the

Kennebec. Four local rivers join them here in Bowdoinham, waters

rising with the tide up the Sagadahoc, and swirling like a maelstrom

out The Chops. This convergence is an emblem of the American experiment.

Diverse cultural streams spiraling together in a noisy tiderace.

And, because each of us must now create his own religion, find

his own sacred symbols, make his own piece with the landscape,

I'll start here, at the center of the universe, where all the

waters meet.

The Corn Peoples sanctified their places by acts of will. Carving

petroglyphs, marking precincts, building pyramids, situating their

dwellings to the sacred directions, enacting rituals. There is

no divine in the landscape unless we see it there. Act it out.

That's part of heaven's deal with man. So it's up to us to put

the sacred back in the woodlot.

Weird

Looking for symbols to reenchant this place after the millennium,

I thought about Weird Eddy. He's the water Coyote. The one who

blows your hat off, and spins your boat around. A spirit of confluences.

Playful and dangerous, like many trickster deities. I decided

to make his mask. Start at the swirling center.

Roughed out a cedar blank, to find two knotholes exposed. One

about right for an eye, but the other, smaller one, somewhere

near his mouth. I imagined some sort of spiral motif, maybe with

the twisted nose of an Iroquois false face. Sketching on the wood

I suddenly saw a spiral rising from the eye and resolving into

an eel, with the other knot for its eye. The Bay is full of eels,

so that fit. Then a counter-spiraling eel entangled. At this point

Seth and an artist friend barged into the shop. Why don't you

make his nose come right out of the mask, they proposed. And the

second eel broke surface.

Eddy