Sagadahoc Stories 140: 11/12/05

On Narrative

| As a young man I thought I’d be a writer. I knew I had the gift of gab, and was excited at the prospect of capturing the world with words. I imagined finding just the right phrase to elucidate each passing moment. I would provide the words to tell the times. My heroes were the likes of Tom Wolfe and Jimmy Breslin and Max Lerner – that tribe of columnists who told us what the world was up to. What we were thinking, or not. |

I was facile enough for straight reporting, turning daily events into inked narrative, but my ambition was to coin phrases that would reveal us to ourselves. Max Lerner had called the excesses of the Cold War “overkill,” and I aspired to be as adept.

|

| I sought for the same telling phraseology in books and music. Tom Wolfe’s sociological commentary flipped my wig, and Menken was a god. I was getting my cultural news from syndicated columns and vynal. Bob Dylan had taken Woody’s topical narratives and plugged them into Rock and Roll. The Booboisie didn’t know what was going on here, did you, Mr. Jones? But I was hip, and intended to tell it like it was. |

| As for novels, I wanted yarns that offered philosophical insight, or a least a sense of looking down from the mountain. There was an old man portrayed in Malraux’s Man’s Fate who epitomized this perspective for me. In the midst of politics by assassination he had an aloof wisdom. That’s the hill I wanted to sit on. |

But Fortune, as the poet said, had other cookies to

hand out. The three years I spent in New York as a working journalist

left me flabbergasted at my own chutzpa. At one point, at the age of

19, I was the nationally quoted source for insight on the Federal Reserve

Bank – and I didn’t know diddly about the Fed. Maybe knowing

nothing is the best vantage for pure reportage, but I was embarrassed

by my ignorance. I decided I had better learn something about life,

if I were to write about it. |

| And there was Viet Nam, of course. So I enlisted in the Navy, and set off on a very different journey. Still I nurtured that old flame, thought of writing a novel full of experience, and (of course) wisdom. I might be less quick witted than that callow boy reporter who mistook sarcasm for wit, but I could still turn a phrase on its ear, and I sure had tales to tell. I just was too busy living them to type. |

| I was reminded of this recently, when Jim Torbert asked if I’d read any Don Delillo. I’d attempted to read one or two of his books back when they were new, and found I couldn’t get into them, but I decided to give them another try. I picked up White Noise. And there was the kind of novel I’d imagined, as a young man, I’d write. Chock full of wonderful plumy phrases, witty characterizations, and cogent cultural observations. And it didn’t work for me at all. I felt distinctly uncomfortable reading the book, and was completely disappointed by the end – a whimper. |

|

Still, here was an author masterfully doing what I’d once hoped to do. So I tried Cosmopolis and Libra. I found Cosmopolis so clever as to be unreadable, but Libra grabbed me. Delillo’s fictional account of the JFK assassination brought me near to the excitement I’d felt reading Malraux back in the 60s. His gift of the telling phrase and sharp description didn’t devolve into a gallery of quips, because the novel was relentlessly plot driven. Maybe the plot was an excuse for the wide angle views, but the luscious phrases couldn’t stall the story. |

| The penny dropped for me. I had thought the purpose of books was to offer distilled insights and philosophical understanding. I keep going to libraries and book stores to find The Book that will take me to the top of the mountain. That was the sort of book I wanted to write. But the books I always enjoy are great stories. Is that the message? It isn’t about the abstract insight, it’s about the story! |

| Is that the ultimate insight? Life is about the living. Hooo. That puts

a whole new spin on this journey. If the quest isn’t for absolute

understanding, maybe what we really hunger for is experience. Certainly

I only know my past as the stories I can tell. Any descriptive generalizations

are beside the point. And how fulsome can you get about a fool’s

errand? |

I still crave some insights in the narrative, and a occasional glimpse over the tops of the trees, but maybe I can be content to just live this yarn – and tell lies about it later. |

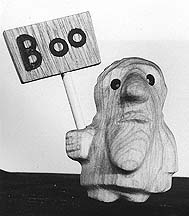

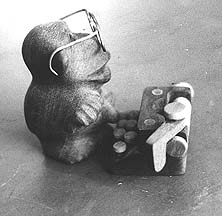

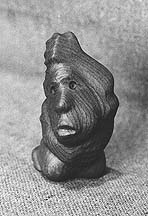

| So much for writing that great book, though. Lucky thing I’ve found the carving, which lets the telling material move through it without much rational help from me. I continue to write, to know what I think, but I may stop reading novels to know what to think. And just enjoy the narrative. |